A legendary wine tasting experience discusses the merits of “natural wine.”

By Randy Caparosso

The Lodi-based Victor Book Club has been around for less than five years (and during the first two years, it wasn’t called anything). It may not last much longer than that because, well, times change, people run out of steam or recalibrate, and all groups go through permutations. The Victor Book Club may even become mythical — something existing as a figment rather than actual phenomenon — and, therefore, something that might as well be talked about now, while it’s still happening.

The Victor Book Club has been taking place at the Victor, Calif., home of Turley/Sandlands winemaker Tegan Passalacqua, who fastidiously cultivates friends and colleagues of like mind from places as far flung as Napa Valley, Sonoma County, Santa Cruz Mountains, Santa Barbara, or even New Zealand and South Africa — all finding their way to sleepy old Victor.

Whatever its history or fate, this loose-knit group of industry wine professionals has managed to evolve into something of a subculture of surprising influence well beyond the scope of Lodi (a wine region that, ironically, is still looking for some semblance of its own place and identity within the global community of other wine industries, or in terms of wine appreciation around the world).

Setting the scene

The Passalacqua abode itself is tiny; so tiny that when Passalacqua puts out a table for his guests, it takes up the entire kitchen and living room. And that’s just for 10 or 12 people.

Mr. Passalacqua keeps so few actual utensils in his Lodi home that he usually has to stand up and rewash forks, knives and plates for second or third courses. Friends always joke about Passalacqua’s idea of healthy eating — it’s called a “meat salad,” because it consists entirely of thin slices of beef (usually Wagyu level) grilled over oak barrel staves just outside the backdoor. For appetizers, he opens up tins of gourmet anchovy, washed down with Grower Champagne. On occasion, to attain some kind of balance, I’ve had to drag my own wooden bowl from home along with accouterments for Caesar salad, which Passalacqua then forces me to prepare “tableside,” as if I were still a waiter in a French restaurant wearing a prom suit.

There’s usually music blasting from a high-tech record player, which Passalacqua dotes on as if it were a beloved big-horned Victrola. He thinks nothing of forcing members to listen to personal favorites such as Boz Skaggs’ “Pain of Love” and Dwight Yoakam’s “Streets of Bakersfield” or his version of Purple Rain, several times a night.

Passalacqua’s house, Passalacqua’s rules.

A different way of talking about wine

Even the name of the group is somewhat dubious. Although Passalacqua is quite the scholar, viticultural historian and intellectual — he likes nothing better than to pick up a textbook on grapevine husbandry published 50 or 100 years ago, and start reciting passages as if his gatherings were an actual book club sharing Italian poetry from the 13th century. But, truth be told, 99.9% of the minutes of a Victor Book Club meeting is devoted to wine tasting. Lots and lots of wine tasting. Typically, two or even more bottles per person.

This is not, mind you, Bacchanalian. It is more like a Platonic symposium, replete with vinous dialog. Although not an actual “book club,” in fact, the soul of it is bookish in its studiousness.

That is to say, the Victor Book Club’s notoriety has grown far beyond the scope of its actual “membership,” mostly because of what it stands for: a different way of looking at, and talking about, wine appreciation. If anything, this involves a lot of talk about “sense of place” in wines — what wine geeks and people with European tastes in wines think of as terroir, whether or not they use that word. Victor Book Club members appreciate the taste of places in wines grown all around the world, although what brings them together is, well, the very idea of meeting in an obscure, little pocket of Lodi called Victor.

The Victor Book Club probably doesn’t exist without the pervasive sense of “Lodi” — practically another word for “underappreciated,” “unknown,” or “well worth exploring.” At the very least, Passalacqua’s own fervent belief is that wines grown in Lodi are just as capable of capturing a sense of place as any other wines in the world.

Blind tasting and terroir

The Victor Book Club, if anything, is a place where alternate wine styles are shared and contemplated. “Transparent” is often a word used to describe these wines. That is, wines grown and crafted to express their origins — not just intellectually, but on an actual, tangible, sensory level.

One of Passalacqua’s favorite things to do is to require members to taste wines “blind.” Which is why a meeting of, say, just eight or 10 members usually ends up with as many as two dozen opened bottles. Of course, members must guess what each wine is. The overriding objective, if anything, is to detect some sort of “sense of place” in the wine, which cannot be done by identifying grapes from which wines are made since most of the world’s finest wines are made from pretty much the same dozen or so varieties.

Syrah, for instance, can be successfully grown in South Africa, South Australia, up and down the West Coast and, of course, in its original home in several parts of France’s Rhône Valley. It is not enough to taste a wine blind and say “Syrah!” You must be able to taste, say, non-fruit elements such as specific manifestations of earthiness, as well as delineate varying levels of acidity, tannin, alcohol and oak, in order to take a good stab at where the wine actually comes from.

This, in a way, addresses the priority of Victor Book Club members: that is, their appreciation of the places where wines are grown, rather than the quality of just grapes or grape growing.

Why is this important?

The wines that most American consumers find in our grocery store shelves or stocked in big box stores are, in fact, products made to fulfill the current predominant market taste for full-bodied, fruit-driven wines. This has come about because, over the past 40 or 50 years more than 60% of all wine sold in the United States are grown and produced in California — and most California wines are designed to meet exactly what the average consumer expects out of them.

A White Zinfandel and Moscato, for instance, should be light, fruity, a little sweet and fluffy. Cabernet Sauvignons, much dryer, heavier, laden with oak flavor. Pinot Noirs, dry yet softer, more fragrant. Pinot Grigios and Sauvignon Blancs, lemony tart and dry. Chardonnays, fuller bodied yet buttery soft and rounded.

There is, however, a tiny yet growing movement of craft style wineries or brands that are finding more and more commercial success by going the opposite direction — producing wines that are less predictable, sometimes achieving profiles or a “sense of balance” that are the opposite of wines made in mainstream commercial styles.

Some of these small, handcraft producers are even exploring a niche that most of the conventional wine industry still considers something of a swear word — so-called “natural” wines. None of those associated with the Victor Book Club are actually trying to be “natural,” they just are — producing wines that are native yeast fermented, generally unfiltered and handcrafted with minimal input, almost entirely for aesthetic purposes. They just want their wines to taste better.

The positive thing about this slowly-yet-steadily growing movement is that when wines are made in this fashion, they are bound to express sensory characteristics reflecting vineyards or regions, not just the work of human hands. These wines tend to be more terroir-focused because you’re also more likely to pick grapes lower in sugar and higher in acidity so as to execute low intervention wine production, which requires a minimalizing of potential issues such as microbial spoilage, oxidation, Brettanomyces, stuck fermentation and so on.

Some of these small, handcraft producers are even exploring a niche that most of the conventional wine industry still considers something of a swear word — so-called “natural” wines. That’s not so much wines made sulfur-free, but rather wines that are native yeast fermented, generally unfiltered and handcrafted with minimal input. Less scrupulous marketers are even calling this “clean” wine. Marketers who are a little smarter are trumpeting the lower carbon footprint of these wines, especially when they are sustainably grown, as a way of appealing to the growing consumer concern over climate change.

Getting technical

When grapes are picked at lower sugars, they’re also more likely to produce wines with less fruit expression, much less or no oak influence, yet possessing more mineral or earth-related sensations which, on an aroma/flavor level, can also be associated with “sense of place.” This is different from most commercial wines, which are based upon predictable fruit-related qualities (i.e., varietal character) and brand styles. In other words, these wines are being crafted to meet newer definitions of “balance,” to be truer to terroir, rather than to achieve arbitrary notions of balance.

Yet these wines can be very original; mostly because when you let vineyards decide the direction of a wine, the chances of that wine achieving a unique profile are increased simply by the fact that no two vineyards, nor two regions, are exactly the same.

This is, in fact, a more European approach to wine production — something that might be considered unconventional by predominant American standards, but that’s very much mainstream in terms of European traditions. What’s new to most of us is “old hat” across the pond. The Europeans have been appreciating wines made in this fashion, like, forever.

Back to the book club

The wine industry, ultimately, is really no different than any other industry. As Americans, we like predictability, but we also appreciate originality. We like our products to be dependable, but we also want them to be new, exciting, innovative…different. And because no two vineyards are really alike, wine can be a perfect way to fulfill this basic, human longing for differentiation, and artistry.

Artistry when it comes to wine, however, is defined as much (or more!) by the vineyards as the people who farm them, and the vintners who craft them — which is why, wine appreciation in America is becoming more fun and interesting than ever.

Fun enough, that is, for professional tasting groups such as the Victor Book Club to begin exerting its modest yet notable influence, not just on one winegrowing community such as Lodi, but also on how wine is thought of across the country and around the world.

To read an expanded version of this article, click here.

_______________________________________________________________

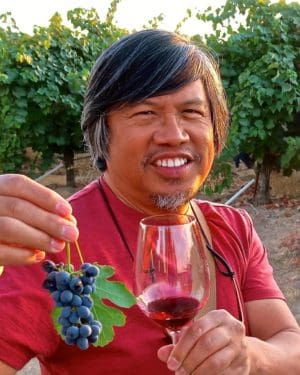

Randy Caparoso

Randy Caparoso is a full-time wine journalist/photographer living in Lodi, California. In a prior incarnation, he was a multi-award winning restaurateur, starting as a sommelier in Honolulu (1978 through 1988), and then as Founding Partner/VP/Corporate Wine Director of the James Beard Award winning Roy’s family of restaurants (1988-2001), opening 28 locations from Hawaii to New York. While with Roy’s, he was named Santé’s first Wine & Spirits Professional of the Year (1998) and Restaurant Wine’s Wine Marketer of the Year (1992 and 1998). Between 2001 and 2006, he operated his own Caparoso Wines label as a wine producer. For over 20 years, he also bylined a biweekly wine column for his hometown newspaper, The Honolulu Advertiser (1981-2002). He currently puts bread (and wine) on the table as Editor-at-Large and the Bottom Line columnist for The SOMM Journal (founded in 2007 as Sommelier Journal), and freelance blogger and social media director for Lodi Winegrape Commission (lodiwine.com). You may contact him at randycaparoso@earthlink.net