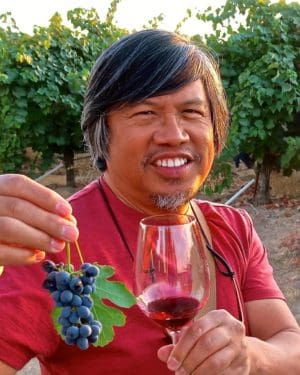

—Randy Caparoso

Does wine-related terroir exist anymore?

This is a valid question, even if a silly one. Of course, terroir exists. If it doesn’t, entire belief systems built upon the premise that terroir accounts for not just sensory differences but also quality distinctions—such as in Bordeaux’s Grand Crus classification, or Germany’s hierarchy of Qualitätswein—would come crashing down upon us. How embarrassing, at least for us wine traditionalists.

But maybe, as Randy Newman once sang, we’re dead but we just don’t know it. That is to say, our senses have become deadened, that soil can indeed exert both quality and taste differentials—despite the related argument recently aired in certain circles that soil cannot impact “flavor” in wine, at least in terms of direct uptake via vine roots.

Let’s get this straight: No one is saying that rocks or dirt in the ground have a direct influence on flavors ultimately captured in a wine. But we (terroirists, that is) are saying that soil content matters. It’s pretty much established, for instance, that high pH calcareous soils, like what you find in Burgundy or Paso Robles, have an inverse impact on pH in grapes—hence, on resulting wines. Calcareous soils, in other words, tend to produce wines with higher acidity than non-calcareous soils. This is science, not fiction.

These observations are borne from observations that are, literally, as old as the hills of France’s Chablis, with its highly calcareous, fossilized oyster shell soils. Try as anyone might, no one in, for example, the Côte de Beaune can ever produce white wines as tart, minerally or delicate as those of Chablis. Vice-versa: it is impossible to produce a Chardonnay-based white in Chablis that is nearly as round, opulent or full bodied as those of Puligny-Montrachet. Yes, climate has a lot to do with the differentiations, but soil is also a big part of terroir in terms of the sensory profiles of resulting wines. The proof is in the Burgundy.

What has made the waters murkier, however, are recent observations that in many parts of the New World terroir is simply not that important when it comes to sensory qualities imparted on commercial wines. In a lot of ways, this is true. Wine production and new-fangled viticulture can indeed trump any factors related to terroir, especially in wines blending grapes from multiple regions. In California, for instance, which is the largest wine producing state., capturing “varietal character” as well as consistency of brand styles remain the predominant factors determining the taste of most wines.

The way we market and sell New World wines, particularly through numerical ratings, has further skewed the way we look at all wines, even those grown in the Old World with their quaint, arguably antiquated, notions of terroir. Unquestionably, having a high “score” has become as good an attribute for a wine as anything on a sensory level. This is the way the commercial wine world now turns. This has created dichotomies—such as terroirists vs. modernists; “natural” vs. “conventional”—seen today. Consumers, media, and wine industry trade and professionals alike are dutifully choosing sides. People can no longer pick and simply enjoy a wine, they want to pick a fight.

There is a longtime California winemaker named Larry Brooks who, in fact, readily admits to being part of the recent wine industry movement that has, in many ways, systematically taken terroir-based belief systems apart. “I am beginning to conclude that improvements in technique will be the death of terroir,” he once wrote to me; citing well known experiences of winemakers in Côte de Nuits taking Pinot Noir picked in Côte de Beaune and making them taste like Côte de Nuits—mostly in order to garner higher scores and prices.

“Terroir is elusive,” he says. Subtle and difficult conceptually, but just because it is subtle does not mean it is not real.” If we take Brooks’ words to heart, we need not feel discouraged that vineyard or regional distinctions have become blurred, or less meaningful. Yet sometimes it is not winemaking techniques that are blurring distinctions. It is the eye of beholders.

Once, for a blind tasting report on Sonoma Coast Pinot Noirs I put together for the first iteration of Sommelier Journal: a panel of five top sommeliers encountered one wine that was an ultra-dark, almost ferociously fruit-forward expression of the varietal. The wine was summarily dismissed by our panelists for being, in their words, “over-extracted” and “obviously manipulated.” One Master Sommelier called the wine “anything but natural.”

The problem? That particular Pinot Noir turned out to be crafted by a producer who is a poster child for “natural,” respected throughout the industry for picking early and producing wines with lower alcohol and balanced acidity. He employs native yeast, uses unfiltered/minimalist techniques in the winery, and is strictly organic in the vineyard. It wasn’t the wine that was manipulated, it was our panelists’ perception of what constitutes manipulation.

Therefore, when confronted with a Pinot Noir from a Sonoma Coast vineyard that happens to grow dark, fruit-forward wine, these sommeliers could not separate winemaking from terroir; mostly because they assumed that fruit intensity, when it is found, doesn’t come from a vineyard—or at least not one falling within their sphere of comprehension. That’s how far this hypothesis has come along, even among geeky professionals: That even artisanal, minimal intervention wines (at least in the New World) are still shaped by wineries or winemakers and not by environmental factors (i.e., terroir).

As wines such as California-grown Pinot Noir do indeed get bigger and darker, whether naturally or through conscious manipulation, it may seem that conceptions of terroir are slipping from our grasp. Is it our wines that are changing, or our perceptions or intellectual grasps? Then again, since when are our best wines ever simple, or predictable? By definition, good and interesting wines should be vexing, or confounding. They should challenge our senses, even surprise us, and end up teaching us more than what we knew before.

As the respected French perfumist Alexandre Schmitt reminds us, “Wine judging is a subjective phenomenon.” It can never be separated from individual perspective. Yet a wine is what it is, no matter what perspective we bring to the table. Or as Schmitt contends, “An assessment may be erroneous, while the sensation itself cannot be.”

Sensory manifestations of terroir, by the same token, will probably always be there—at least in our best and most interesting wines. Whether or not we are willing (or able) to perceive them.

_______________________________________________________________________

Expert Editorial

Randy Caparoso is a full-time wine journalist/photographer living in Lodi, California. In a prior incarnation, he was a multi-award winning restaurateur, starting as a sommelier in Honolulu (1978 through 1988), and then as Founding Partner/VP/Corporate Wine Director of the James Beard Award winning Roy’s family of restaurants (1988-2001), opening 28 locations from Hawaii to New York. While with Roy’s, he was named Santé’s first Wine & Spirits Professional of the Year (1998) and Restaurant Wine’s Wine Marketer of the Year (1992 and 1998). Between 2001 and 2006, he operated his own Caparoso Wines label as a wine producer. For over 20 years, he also bylined a biweekly wine column for his hometown newspaper, The Honolulu Advertiser (1981-2002). He currently puts bread (and wine) on the table as Editor-at-Large and the Bottom Line columnist for The SOMM Journal (founded in 2007 as Sommelier Journal), and freelance blogger and social media director for Lodi Winegrape Commission (lodiwine.com). You may contact him at randycaparoso@earthlink.net.